Coins And Fallacies In The World Of Infrastructures

How flipping a coin can bring our Infrastructures to collapse. Or: the Black Swan and the wise decision-maker

September 17, 2017

Reading is always good

This post is not my typical Data Science project, but rather an opportunity for reflection. All good reasons for you to continue reading!

A friend of mine working in the field of Risk Management pretty much said that he owes it to a specific book if his career led him where he is now. This book is The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, by the American-Lebanese statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb. It is frankly quite hard to categorize the book as it is to categorize the author, but suffice it to say that it is a thought-provoking journey into the concept of Black Swans - events with low probability of occurring and disproportionately large impacts.

Civil Engineering Infrastructures belong in Extremistan

Dr. Taleb states that Black Swans are a daily feature of Extremistan, an idealized world where the impact of an event is vastly superior in magnitude to the probability of that event occurring. You drop your sandwich, it lands with the butter-side down, you slip on that, and it all escalates. I can recall quite a few events involving Infrastructures that happened in a less idealized world:

- The I-35W Mississippi River Bridge collapse in Minneapolis (2007);

- The King’s Cross fire in London (1987);

- The St. Francis Dam failure in Los Angeles County (1927).

Now, either there is something disturbing about years ending in 7, or our Infrastructures are an easy prey, as the list goes on and on (the latest entry being the unfortunate Grenfell Tower fire). In each one of these examples, an apparently meaningless event escalated into dramatic consequences: the neglected corrosion discovered on the pillars of the Mississippi River Bridge, the match thrown onto the wooden escalators at King’s Cross as a result of an ignored ban, and the cracks on the surface of the St. Francis Dam that William Mulholland himself dismissed. Drop, butter-side down, slip. Repeat.

Tony vs Dr. John and the flipping of a coin

As per the book, the good Dr. Taleb has two friends: Tony and Dr. John. Tony is a self-made man and an accountant who rose to success by “reading the situation” and contextualizing. He has no formal education, but claims to be able to interpret the human species. Dr. John is an Electrical Engineer with a PhD, and it is his scientific and methodical mind that guides him through the day.

Tony and Dr. John meet one day. In front of them, Dr. Taleb is going to toss a coin 100 times. The penultimate toss gives heads, making it 99 heads in a row. At this point, Dr. Taleb asks his two friends to predict the next outcome. Tony says that there is something “loaded”, e.g. the system is rigged and it does not play out fairly; as such, he gives tails no more than a 1% probability. Dr. John, realizing that the flips are independent events, says that it is going to be either heads or tails as both have a 50% probability.

Why I disagree. Or: the quest for a wise decision-maker

Dr. Taleb infers that Tony is thinking outside the box, because he infers his prediction by reading the situation, bereft of preconceptions. Dr. John, instead, relies too much on pre-fabricated models and does not venture outside his comfort zone. The conclusion is that Dr. Taleb would totally follow Tony’s indications if he had to make an investment.

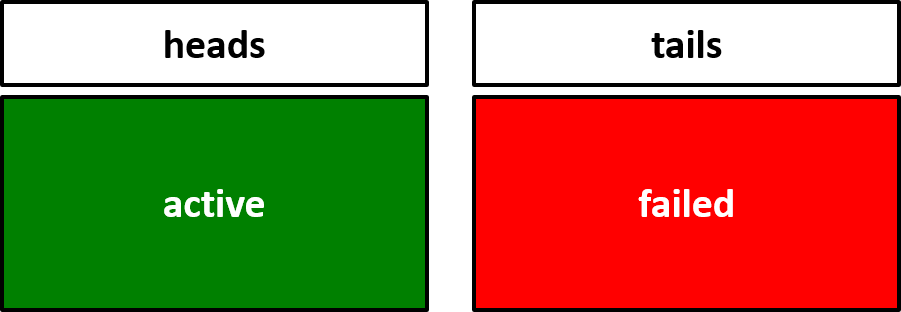

Now, let’s assume that the outcome of the toss is in fact the status of an infrastructure:

I can see a huge fallacy in Dr. Taleb’s argument if I try to apply the same reasoning to the world of Infrastructures. If we reinterpret the coin toss experiment, our infrastructure has performed and delivered without any service failings 99 times in a row. Notwithstanding my sympathy towards Tony - he had the guts to move from Brooklyn to New Jersey and commutes every day in his Cadillac -, I can see why he would be a terrible decision-maker. Saying that he gives tails no more than a 1% probability of occurring sounds to my ears as if he is underestimating the occurrence of a failure. The fact that never, in the previous 99 tosses, has he seen tails gives him enough confidence to basically rule out the failure, the Black Swan if you will, and if he were to adopt strategies to cope with such rare event, he would probably argue that it is a waste of money. We can argue that this will increase the exposure of our infrastructure to the risk of failings, with all the ensuing monetary costs.

On the other hand, Dr. John’s approach would probably make him a better decision-maker, as he keeps the door open to Black Swans. Using Dr. Taleb’s definitions, Dr. John is not influenced by the confirmation bias, which makes us rule out events that we have never witnessed. He does not even listen to the voice of the narrative fallacy, which would make us infer that an event will not happen because it has never happened.

Let’s not have decision-makers tossing coins

In retrospective, I can see many little Tonys behind the spectacular failures of our Infrastructures. Sometimes it was just one Tony, as was the case with William Mulholland underestimating the role of superficial cracks on the St. Francis Dam. Sometimes it was many individuals, as many are possibly to blame for the King’s Cross fire and for not adopting what-if regulations that might have prevented the accident. The last circumstance offers those responsible the vane consolation of co-responsibility, but it does not make the event less impactful. There are quite a few arguments that might be thrown at Dr. John, one being that the 50% chance is a fairly inaccurate measure and it is not financially wise to overestimate any risk. I agree with that, and I would speculate that it is up to solid models to try and estimate a more accurate risk. However, I would also argue that we should take all coins away from decision-makers, so to shield our communities from biases, fallacies, and why not, Black Swans.